+ + + + + + +

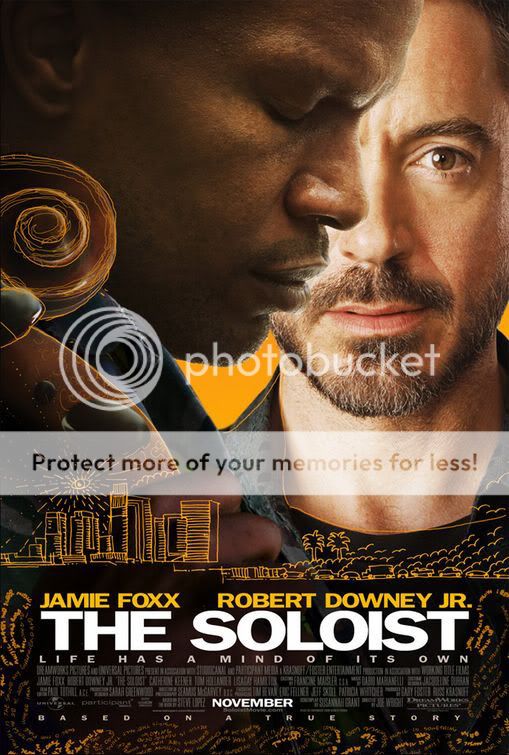

Struggle and Rescue, a Duet in Sharps and Minors

By MANOHLA DARGIS

Published: April 24, 2009

Some of the lost souls in “The Soloist,” a big studio movie about a one-man rescue mission, look as thin as the crack pipes clamped between their lips. These are a few of the ghosts who haunt Los Angeles, that Mecca of Fabulousness where you can go for weeks (and invariably by car) without smelling the reek of other people’s desperation. That helps explain why Hollywood types tend not to set their camera sights on homeless men, women and children, unless they’re good for a little uplift (as in the Will Smith vehicle “The Pursuit of Happyness”). Homeless people are generally, pardon the pun, bummers —they also can’t afford tickets.

Based on a book by the Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez, “The Soloist” recounts what happened when one of the city’s more privileged denizens (Robert Downey Jr. as the newsman) met one of its least fortunate (Jamie Foxx as Nathaniel Anthony Ayers). A Juilliard dropout, Mr. Ayers ended up on the streets, where he pushed a shopping cart filled with trash and bedded down next to rats. This isn’t a milieu in which you might expect to find the British director Joe Wright, last seen exploring class and other catastrophes in “Atonement.” Yet he fits fine with “The Soloist,” perhaps because he brings an outsider’s perspective to the material or is just accustomed to navigating the divide between the haves and have-nots.

Polished to a high gleam by Mr. Wright and written by Susannah Grant (whose credits include “In Her Shoes”), the film is imperfect, periodically if unsurprisingly sentimental, overly tidy and often very moving. It works hard to make you feel good, as is to be expected, even as it maintains a strong sense of moral indignation that comes close to an assertion of real politics. Outrage would be too much for a mainstream entertainment like this one to manage. Like its muckraking journalist guide, it exploits its subjects for its own purposes. But its commitment to the material feels honest, nowhere more so than in Mr. Downey’s darkly shaded, nuanced performance, one that deepens this film with its insistence on the fundamental mysteries of human character.

It’s no surprise when Lopez, taking a break from the newsroom roar, stops to listen to a disheveled man playing a two-stringed violin. In journalistic fashion, wonderment morphs into curiosity and then dogged pursuit as he quickly grasps that he’s discovered the makings of a great story. Although Lopez cooks up a column soon after they meet, the full account of how Ayers went from a happy childhood in Cleveland to bright promise in New York and then to his Los Angeles hell emerges through seamlessly interspersed, economical flashbacks. Lightly tinted, as is often customary in movies that return to the past (it’s as if happy childhoods were bathed in honey), the flashbacks are pieces of a puzzle that Lopez becomes increasingly hesitant to solve.

It is, he discovers, difficult to deal with people in pain. Although they meet cute in the shadow of a looming statue of Beethoven (dedicated to the founder of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra), the journalist and his story don’t settle into predictability, largely because Ayers is intrinsically volatile. Given to verbose bursts and abrupt silences, he doesn’t so much talk to Lopez (he doesn’t always make eye contact either) as just talk and talk, the words pouring out like water until something (rage? fear? chemistry?) stops the flow. Mr. Foxx often seems uncomfortable in his role, wavering between pathos and something harder and truer, but his scatlike delivery of some of Ayers’s twisting ropes of words can be mesmerizing.

In Los Angeles homeless people are more likely to get sunburns than die freezing in the streets. Because of the city’s sprawl and dependence on automobiles, they also tend to be less visible than they are in more geographically compressed urban areas like Manhattan. In 2005, the year Mr. Lopez wrote his first column about Mr. Ayers, an estimated 8,000 to 11,000 were living in a 50-block skid row downtown, not far from the Los Angeles Times building, City Hall and the Walt Disney Concert Hall, the Frank Gehry-designed music center that sits on a hill like an enormous silvery flower far from the reach of the Nathaniel Ayerses of this world.

Over the course of “The Soloist,” Lopez helps Ayers reconnect with his music and, in tentative fashion, a more dignified way of living in the world. There are triumphs and setbacks, but these arrive fairly quietly, with none of the 101 weeping strings that often come with stories as emotionally fraught as this one (though Beethoven does shake the speakers). Helping someone off the streets is no small thing, but the story of one man is just that: the story of a single individual, a point that Mr. Wright underscores repeatedly. Again and again the film plunges into the streets, diving into a brackish humanity only to then drift amid the lost and forgotten. In the restrained voice-over that wends through the film, Lopez gives witness to what he has seen.

“The Soloist” wouldn’t work half as well without Mr. Downey’s astringent, bristly take on a man whose best intentions eventually collide with difficult truths. The actor is a wonder, but he has solid support from Catherine Keener as Lopez’s former wife and editor and Nelsan Ellis as a counselor working in the skid row trenches. Both characters exist mostly to push back at Lopez: they wag an occasional finger and dole out tough love and advice. Mr. Wright might be tempted to indulge in lofty symbolism (there are some unfortunately high-flying pigeons), but these three actors, along with the homeless people who worked as extras, help keep him tethered closer to the ground. It’s amazing what you can see when you get out of your car and walk: other people, for starters.

“The Soloist” is rated PG-13 (Parents strongly cautioned). There’s nothing here that a 13-year-old hasn’t heard.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น